The crummiest part of venture capital is having to tell people no. We, like many other early-stage deep tech funds, often need to make tough decisions, and can often with the resources we have only invest in less than 1% of the companies we connect with.

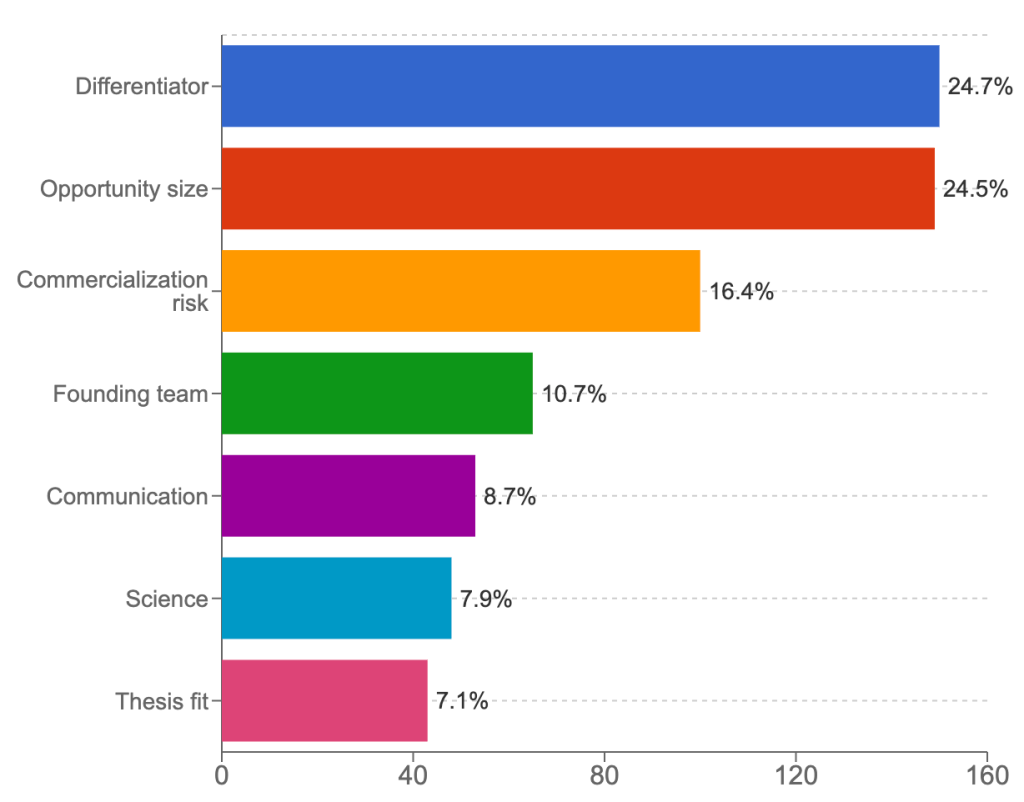

I thought it would be helpful for founders to understand better what deep tech VC funds like us are looking for, and went back to our notes on the last ~500 startups we met. I could boil down our feedback to 7 main factors, which I think are critical.

Really hope this info will be helpful for teams on what to prioritize and focus on, and will lead to some actionable insights on how to reach the top percentile of startups we and (I think) other deep tech funds are getting excited about.

Most of the data I am sharing comes from companies that applied to SciFounder Fellowship, which is an applications-based investment program that comes with up to $1MM, meaning it applies to early-stage pre-seed and seed startups where the main focus is on the concept, technology, and the founders.

Differentiator

One of the core parts of our model is to back a small number of companies that have the potential to become real outliers: Companies that could change how we treat diseases or reshape scientific or clinical approaches over the next decade. A lot of the teams we meet are working on strong ideas that might perform better than current approaches, but the ideas that really stand out to us are the ones that are aiming for something fundamentally new: a different biology, a new modality, or a novel way to reach tough targets. For example, developing novel bi-specific antibodies against well-known targets, creating more accurate organoid models, exploring CAR-T therapy for solid tumors, or working on computational models for small molecule drug design are all exciting concepts, but being explored by many other well-funded companies, and on their own, often hard to win early stage capital over.

Slides like this are helpful, but often not enough to stand out

Opportunity size

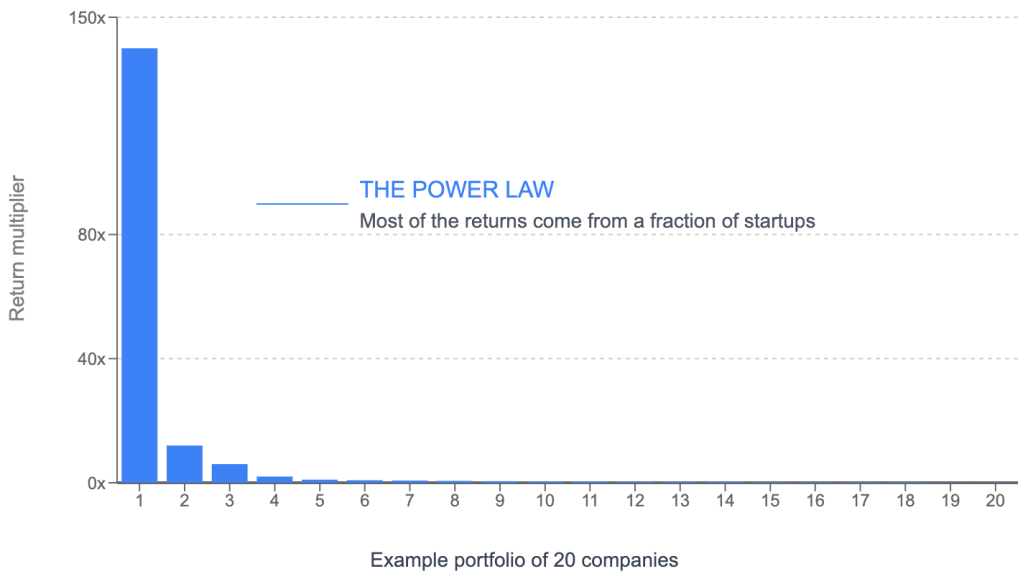

In most cases, VCs raise funding from investors themselves, and their job is to return that funding, ideally at very high multiples. They invest in multiple companies they have high conviction in, with the understanding that most of the investments will fail and that only one or two will break out and make the fund a success. This means investors have to find and invest in companies that truly have breakout potential to carry and return the whole fund. Another challenge is that early investors get diluted by subsequent financing rounds, meaning their initial ownership stake is slashed in half (or worse) at an exit. That’s why early-stage funds like ours need to prioritize companies with massive exit potential, even if that comes with higher technical risk over safer bets with lower upside.

Most startups will fail and every investment needs to be able to return the fund in

Commercialization risk

We’ve seen plenty of exciting technologies, but real-world application or adaptation is often what makes us stay cautious. This comes up less in therapeutics, where the need and solutions are clearly defined, but more so in other sectors. Here are a few key concerns we think about a lot – if you can address them early, you’re already ahead!

Medtech, diagnostics, digital health

- Regulatory approval is half the battle; the final boss is go-to-market – think about a reimbursement strategy early on and get a deep understanding of what providers really want.

- Even with coverage, hospital procurement is slow and relationship-driven – think about the muscle you need to build here, and key hires.

Synbio and Agtech

- Many synbio and agtech products struggle to compete on cost with agrar or petrochemical solutions – what is the scale you need (and is it realistically achievable) to reach price parity?

- Consumers won’t pay a premium for everyday or commodity products – if you’re starting with specialty items, make sure the opportunity is still big enough to matter.

Tool and software companies

- Buying behavior varies widely between academia, pharma, and clinical – if early adopters are mainly academics, what’s the strategy to expand into other markets?

- Early revenue is great, but can be misleading when customers are still experimenting with different tools – how will you achieve long-term adoption?

Biomanufacturing

- Demand in biomanufacturing is lumpy and milestone-driven – how can you survive biotech winters where demand is tightly tied to the financial environment?

- Most manufacturers compete over a few dozen key customers – how can you compete with massive organizations that operate in lower-capex regions?

Founding team

Building a research-heavy company is a marathon. If the founding team isn’t set up with the right roles, structure, and incentives from day one, things will break. Here are a few key points we look for in a founding team and dealbreakers to be aware of:

- Strong technical founders with operational instincts who are ready to commit the next decade to building the company.

- Less excited about founding teams where scientific founders are only part-time and bring in an external CEO with little mission alignment

- Equity splits need to make sense, especially in spinouts, where part-time academics often hold large stakes. If full-time teammates don’t have enough ownership, they might eventually walk if it’s not worth the sacrifice anymore.1

Communication

Most founders we talk with are first-time founders, often from academia or biotech. We don’t expect them to present like seasoned CEOs, but clear, simple communication is still one of the strongest indicators of how well they’ll do with fundraising, hiring, and partnerships. A common pitfall is over explaining or using too much jargon. Strong intro decks stay under 10 slides, avoid detail overload, and hit the key points: problem, solution, market, edge, team, and ask.2

Science

We are scientists and technical operators ourselves and do like to go deep into the technical bits early on. We like challenging projects if the risk/reward ratio makes sense, but will stay away from proposals if we cannot get conviction around the underlying science or if we think there are fundamental bottlenecks that will be very hard to overcome. It’s been very nice to see that technical concerns have not been the main reason for us having to pass on companies and been overall super impressed by the scientific rigor and deep know-how of the founders we had the chance to chat with so far.

Final thoughts

I hope sharing these patterns helps founders better understand how early-stage funds like ours think and what we’re optimizing for. Even great ideas and strong teams sometimes aren’t the right fit for our model, but that doesn’t mean they won’t succeed. The bar is high, but so is our belief in the next generation of technical founders tackling hard problems – and of course, we also get things wrong and miss out on opportunities.

At the same time, I hope these notes are also a helpful mirror, encouraging some of you to step back and ask: Am I working on the right thing? Many scientists default to spinning out their own research, but some of the most compelling companies we’ve seen came from founders who looked outside their own lab, to other departments, collaborators, or overlooked papers.

The best startups often emerge after testing several concepts, learning from what didn’t work, and discovering the one that finally clicks.