Animal toxins are nature’s precision tools, evolved primarily to immobilize, kill, or deter. They hold the largest known arsenal of biological warfare, shaped over billions of years through an endless arms race with their prey to become both highly efficient and remarkably selective. They’re not only a marvel of natural engineering but have also helped scientists develop some of our most effective drugs.

Oral ACE inhibitors, for example, widely used to treat high blood pressure with a cumulative value of around $9B per year, were inspired by pit viper venom; direct thrombin inhibitors 1, critical for preventing strokes and other clotting events and at about $5B in sales per year, were mimicked from molecules found in leech saliva2; one of the first longer-acting GLP-1 agonists, first discovered in the saliva of Gila monsters 3, helped develop today’s GLP-1 drug class, which has now exploded to over $50B per year, making it one of the best-selling categories in medicine.

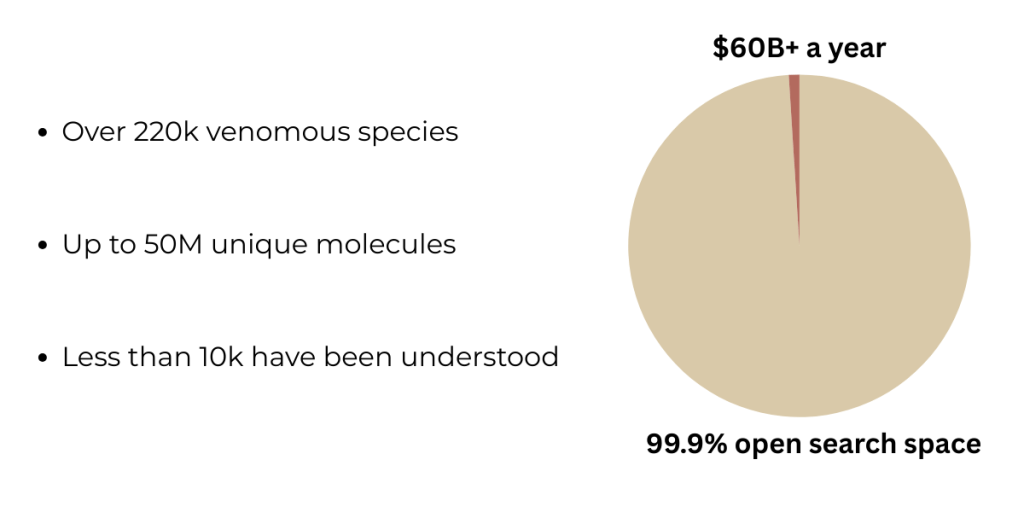

What excites me the most about this topic is that we’ve barely scratched the surface when it comes to mining this massive natural resource of toxins. There are around 220,000 venomous species 4, holding an estimated up to 50 million unique molecules 5, yet we’ve characterized less than ten thousand 67. To put that into perspective, less than 0.1% of this open search space has already led to the development of blockbuster drug classes worth over $60B per year.

Traditional venom mining, though, is slow and unscalable. Venom has to be milked in large quantities, molecules extracted and purified, then reconstructed and synthesized, and only then can they be screened across a handful of targets. This makes digging through such a massive search space nearly impossible and restricts efforts to only larger animals that can produce enough material, leaving most insects, small mollusks, nematodes, and many marine invertebrates largely untapped.

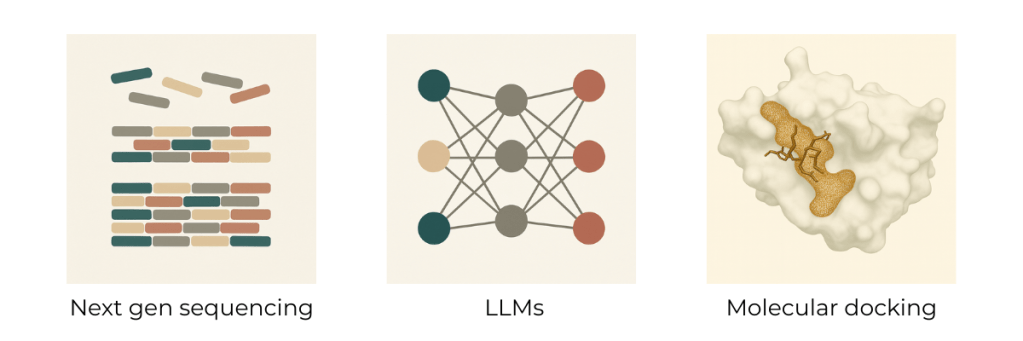

With the advent of powerful next-gen sequencing, LLMs, and physics-based molecular docking screens, I think we now have the tools to launch massive venom mining projects and finally begin tackling this, for now, insurmountable natural library.

While the targets cluster around a handful of protein families, each molecule could still interact with hundreds to thousands of potential targets, which creates a huge combinatorial search space and makes traditional high-throughput screening technically impossible. This is where computational tools start to get interesting. Large language models have by now made their mark in biology and, I think, surprised even some of the heaviest critics. Here, I think specialized models could really shine and significantly shrink the toxin–target search space. On top of that, physics-based molecular docking tools have made strong progress over the last few years and could be an ideal tool for last-mile binding verification before having to move into any kind of wet-lab or animal work. This could save millions of dollars in discovery and development and shrink timelines from years to months, enabling the generation of meaningful hits with exciting therapeutic potential.

I really think it is now prime time to build venom biobanks of unparalleled size and be able to dig through hundreds of thousands of molecules in a very time and cost-effective way. There’s a good chance that through this approach, we might stumble across the next molecule that could become the basis for hugely successful drug classes like oral ACE inhibitors or GLP-1 agonists.

If you are interested in this topic or already working on a project like this, I would love to chat with you. I genuinely believe we’re sitting on a massive untapped biological resource, and it’s time to get the picks and shovels out.

Send me an email at alex@scifounders.com.

- Camargo et al., Toxicon (2012) ↩︎

- Montinari et al., Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy (2022) ↩︎

- Parkes et al., Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery (2012) ↩︎

- Herzig et al., Biochemical Pharmacology (2020) ↩︎

- Ageitos et al., Molecular Sciences (2022) ↩︎

- Jungo et al., Toxicon (2012) ↩︎

- Zancolli et al., Giga Science (2024) ↩︎